November is coming. This year it’s going to be different.

For the last quarter century, every November, I’ve participated in (and won) an annual challenge. I write a 50k word novel in 30 days. This crazy endeavor is known as National Novel Writing Month.

But in early 2025, the Office of Letters and Light closed.

Now, if you go to NaNoWriMo.org, all you’ll find is a Go Daddy domain for rent.

The final years of NaNoWriMo weren’t without controversy. There is no need to go into the specifics. But by 2024 many writers just weren’t participating… at least not in any official capacity. And they were losing sponsors. In early 2025, the organizers reported that it was no longer financially viable, and they had to shut down.

How it Began (for me)

I did NaNo for the first time in 2002. I consider myself an early adopter, since it had only officially been running since 1999. The internet was a much simpler place then. No Facebook. No TikTok. Nearly everything was text based. People had to connect through phone lines. And it was filled with the promise of unrestricted access to information.

In 1999 Chris Baty, a writer from San Fransico, and a few others put together the first challenge. And they stumbled onto something big. In the creative world, “flow” is a state of complete immersion in an activity. Creative types crave this state. It’s exciting. It allows one to generate fresh ideas. And it’s productive. What Baty and his group found was that by sacrificing quality for quantity, they reached into this state of creative flow. Story details were easier to remember. Characters took on a life of their own. And at the end of the month, many of them had written entire novels.

The idea caught on. In 2000, about 140 people signed up. In 2001, they were up to 5000. Then when I joined in 2002, they had 14,000 participants from all over the world.

People starting organizing local events… social gatherings to talk about the writing process, brainstorm, and “write-ins” so they could all write together. Collectively, a procrastination of writers would take over a wing of a restaurant, quietly typing away on their laptops. And saving their progress on 3 1/2 inch floppy disks.

At the end of the month I had 50k words toward a crappy novel.

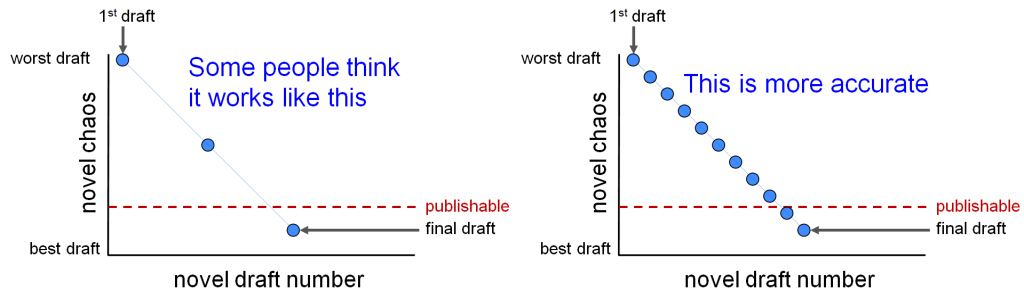

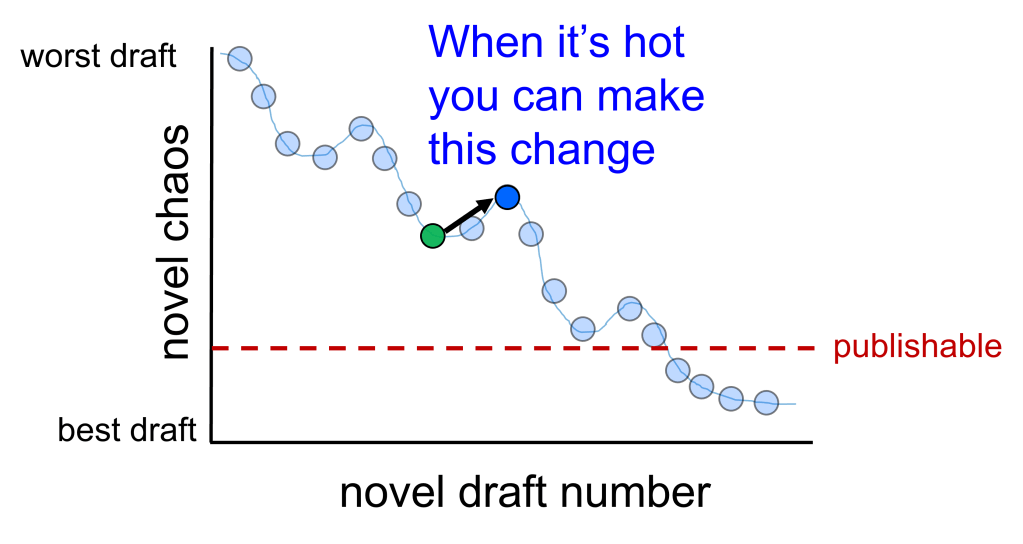

And I mean CRAPPY. A first draft NaNo Novel shouldn’t ever see the light of day. EVER. They’re meant to sit on a hard drive, locked away in the Never Never Land of Stories. Then, there in digital sedimentation, they can be mined for the jewels within.

My first NaNo Novel was the origin story of a modern day ninja. It was inspired by a mix of 80’s Sho Kosugi VHS movies and DVDs like Payback and The Matrix.

Did I mention it was crappy?

Peak NaNoWriMo

I had the fortune to be in Edmonton in the mid-to-late 2000s. A core group of enthusiasts took over the local organization of events brought them up to a “whole ‘nuther level.”

We had plot planning parties, kick-offs with snacks and games, midnight sprints. Some years we organized conference-style workshops, where we would examine story structure and share productivity tips. In October, the online forums would explode with activity. There were hubs for local regions, lounges for your favorite genre and threads where you could read what everyone else was writing. Halloween became NaNoWriMo-Eve. And year after year a core group of writers would return to the exercise, serendipitously generating a community.

For writers, that was huge. Writing is a solitary hobby. NaNo provided a community for a lot of people who otherwise might not have had much social connection at all. (Granted many introverts are just fine with that.) But by 2015, NaNo had over 400k registered participants, and 40k winners!

It carried forward for years. Every November I managed to get my 50k words. By 2022 I had collectively accumulated over 1 million. The books varied. They were all crappy. Most were left unfinished. But the process allowed me to grow as a writer.

One of the great things about NaNo is that you can try out genres you wouldn’t normally spend much time with. Even though I’m primarily a science fiction writer, I’ve tried out action thrillers, fantasies, westerns, and even a horror. Last year I even attempted a romantasy.

We shall not speak of the romantasy, except to say that I brought crappy to a whole ‘nuther level.

NaNoWriMo in 2025

Communities of writers are still out there. If you look for local writing groups, or online communities, you should be able to find others who are still excited about taking on this kind of challenge.

I still am.

You don’t need forums. You don’t need write-ins. You don’t need an Office of Letters and Light.

All you need is a personal commitment to pound out 1667 words per day in November. If you can do that, you’ll have a novel come December 1st.